Common Birds of the Launch

Spring has finally sprung in the Adirondacks, and the air is once again filling with the sound of birdsong. While birds migrate back north and prepare their nests, we eagerly ready our boats and gear for another season out on the tranquil waters. As we embark on our adventures at lakeshores and riverbanks, it is not uncommon for our paths to meet at the launches. Learn more about the birds that share our Adirondack waters below!

Common Loon

The Common Loon is perhaps one of the most well-known birds of the Adirondacks. When not seen, their ghostly calls can be heard across the lake. Loons only come to shore to mate and incubate their eggs, so you are most likely to find them in the water. Their legs are situated towards the back of their bodies, making it hard for them to function on land. What Loons lack on land they make up for as strong swimmers and divers. Loons require lots of room in order to take off. Depending on the wind, a loon could need 30 yards to a quarter-mile for flapping their wings and running on the water in order to take off. They spend their summers, or breeding season, in Canada but coming as far south as the Adirondacks, northern Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine.

Belted Kingfisher

If you’ve ever heard a rattling sound while spending time around streams, lakes, and ponds, then you likely heard a Belted Kingfisher. These birds often call while flying about, looking for fish to dive after and defending their territory. While males are commonly known for being the more colorful bird, in the case of the Belted Kingfisher, the opposite is true. The female is the one with more color, displaying a chestnut-colored band across their lower chest. Their nests consist of a burrow with a tunnel, usually in a dirt bank near water. Belted Kingfishers can digest harder things such as bones and fish scales when they are young, but their stomach chemistry changes as an adult. The adults regurgitate pellets that are often found around their perches which allow scientists to learn more about their diets.

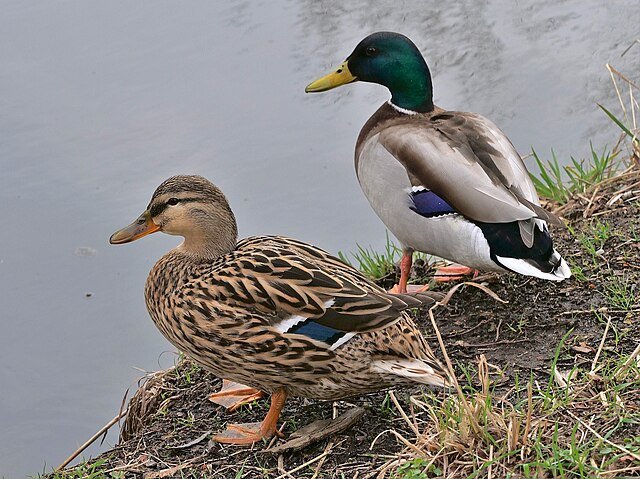

Dabbling Ducks

Mallard, American Black Duck, Wood Duck

If you spend a lot of time on the water, you’ll likely see waterfowl. The most common ducks seen in the Adirondacks are Mallards, the American Black Duck, and the Wood Duck. Mallards are found across the world and are the most frequently seen duck. The familiar quacking sound we associate with ducks come from the female Mallard, while males make a quieter rasping sound. American Black Ducks look very similar to female Mallards, but they have darker colored plumage and an olive-yellow bill. They prefer more protected bodies of water like saltmarshes and ponds, but they do often mix with Mallards, making identification difficult. Where Mallards and the American Black Duck nest on the ground, Wood Ducks nest in cavities, like holes in trees. As natural nests can be hard to find, they are often found in human-made nest boxes. After the ducklings hatch, they jump down from their nest and head towards the water. They can jump from heights of over 50 feet without sustaining an injury.

American Bittern

American Bittern by Walter Siegmund, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The American Bittern is an elusive bird that hides among reeds and marshes, blending in with its mottled brown plumage. To avoid being seen, the bittern will stand motionless with its neck stretched and bill pointed towards the sky. As they do this, they point their eyes downward to look for fish and frogs, giving them a bit of a silly appearance. Male bitterns aggressively establish their territories, responding to the calls of other males from distances of up to 1,600 feet away.

Great Blue Heron

Great Blue Heron by Walter Siegmund, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This graceful bird is often found on the shorelines of various waterbodies, scanning for fish to eat. Great Blue Herons epitomize patience and precision, as their slow movements and waiting lead to a quick strike of their sharply pointed bill into the water to scoop up their prey. They are even able to hunt into the night as they have a high number of photoreceptors in their eyes.

Double-crested Cormorant

These black birds may be easy to look over in the water, but on land with their wings outstretched, they are hard to miss. Double-crested Cormorants are diving birds that do not have as much preening oil as other birds, so they have to dry out their feathers by standing outside of the water with their wings outstretched in the sun.

Bald Eagle

Bald Eagle by Andy Morffew from Itchen Abbas, Hampshire, UK, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Since 1782, the Bald Eagle has held the position of being the national emblem of the United States, but it also serves as a spiritual symbol in indigenous communities. These birds of prey are often found at boat launches among the trees, looking for their next meal. You may think they are hunting or planning on diving into the water, but they actually prefer to let other animals do the work for them. They are known for harassing Osprey, causing them to drop their prey, allowing the eagle to come in and steal it.

The eagle population in the U.S. is healthy and they are a low concern for conservation, but they were once considered an endangered species due to pesticides like DDT. DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) was widely used in the mid-20th century and had detrimental effects on bird populations by thinning eggshells and causing reproductive failure. This led to a sharp decline in bald eagle numbers by the 1960s. Rachel Carson's influential book "Silent Spring" brought attention to the harmful effects of pesticides, leading to the ban of DDT for agricultural use in 1972.

Osprey

Osprey by Russ, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Osprey, another hawk that hangs around the water, are excellent anglers. Their success rate can be as high as 70%. Along with barbed pads, they have a reversible outer toe that lets them grip fish with two toes in the front and the back. When flying, Osprey will rotate the fish so it is head first to cut down on wind resistance. They often build their nests of untidy sticks on humanmade structures like telephone poles and designated nest platforms.